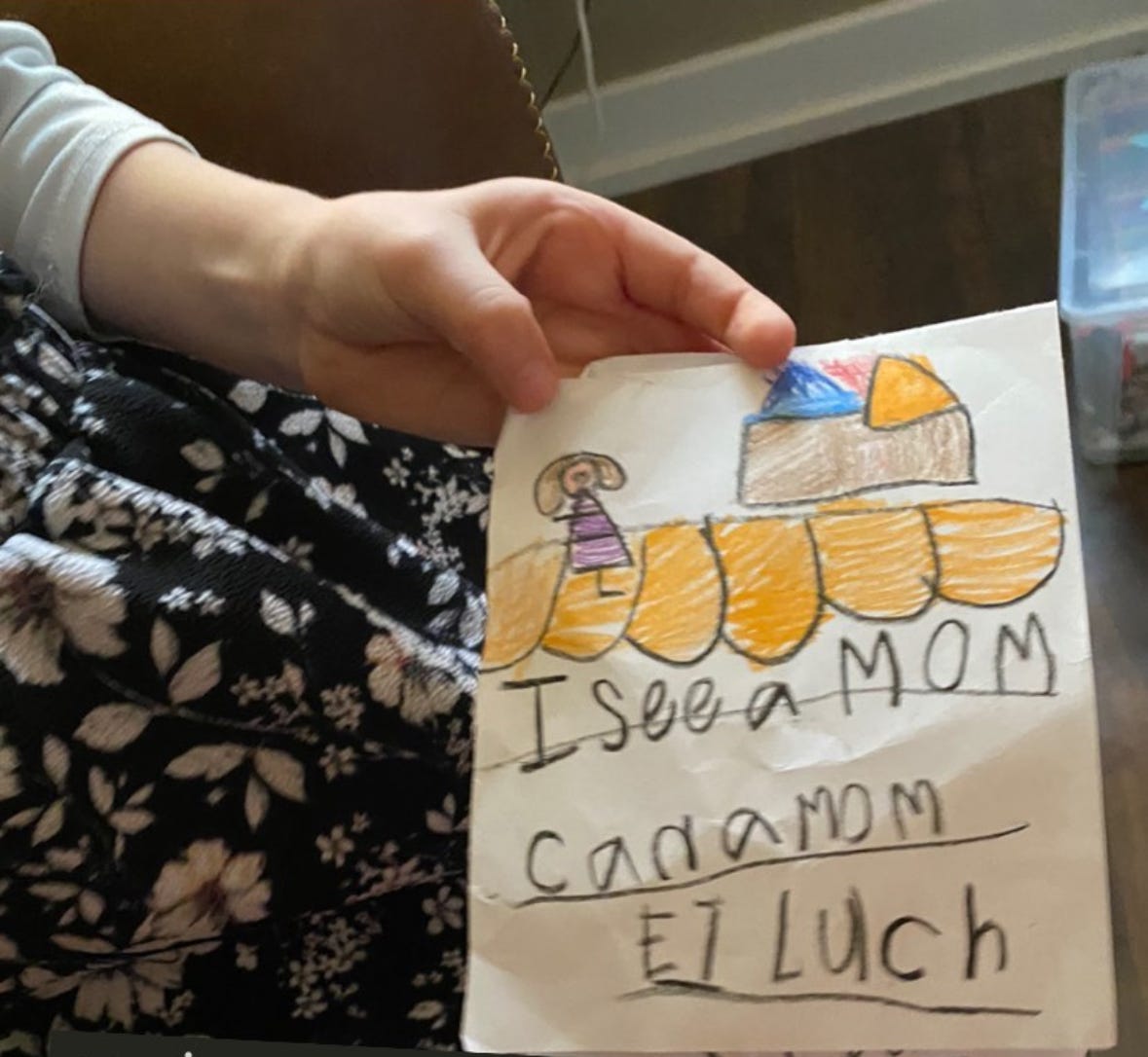

“I see a mom. Can a mom eat lunch?” was written on a scrap piece of paper presented to me by my then-six-year-old daughter at the end of a school day.

She had been building stories in school to replicate the story patterns of Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? during one of the many online school periods of COVID lockdowns. It was one of those moments of immediate pause, to really take in what my actions were demonstrating to her. At this point, I had been working remotely for different corporate and academic jobs for over two years. Through this, she was watching me astutely, learning what makes for “normal” routines through my practice.

Lunch has always felt impossible for me, and I am bad at remembering to eat it consistently. While I always looked forward to it in more physical jobs (lifeguarding, swim instructing, archaeological excavations and other field work), it is otherwise a tricky time of day to get me to eat.

As an anthropologist, I sometimes get in trouble for turning the field’s study of culture inward to Western/white behaviours. That’s what sociology is for, dummy! And with no disrespect to sociology, I think there’s an added layer of cultural behaviours and perspectives that entangle individuals with broader social, political, environmental, and cultural systems in ways worth investigating.

What makes lunch feel so sterile, unnecessary, and laborious within a Western context? Conceptually, lunch is a perfect practice to explore how culturally re-affirmed understandings of time, appetite, and identity play out in the 20th century — particularly with white-collar corporate emphasis on cold, quick, and easy lunches.

grazing plates and brain science

During university years where I lived with my grandparents, they made their meals with such keen consistency, it left me in awe. There was always a TV-worthy breakfast layout, a hot and simple lunch, and a thoughtful dinner. My grandmother would always baulk at my refusal to sit down for lunch — I prioritized studying, getting to my part time job, or just doing anything that wasn’t eating lunch. This has been passed along to any roommates or family I’ve lived with, it’s just difficult to get me to even consider lunch. In school, I’d reject the daily ham and cheese sandwich. In adulthood, I dutifully make my daughter a fulsome lunch but tend to find something a bit more snacky for myself: a spanakopita, a Mr. Shin cup, some fruits and cheeses and crackers and nut butters. Perhaps it’s my own long-standing girl dinner behaviour, but I think there’s more to it.

I toss excuses up, largely around being a “grazer” and having mostly stationary jobs where I don’t exert enough energy in the day to warrant a heavy plate of reheated leftovers. I’ve always felt as though there’s a chip missing in me around eating, or rather the idea of desire and appetite that seems to be non-negotiable for others. In truth, I know there is also the weight of disordered eating frameworks during my earlier years that I will always navigate. I interviewed neurobiologist Jillian Lampert on AnthroDish years ago highlighted why it feels trickier for some people than others to cue their eating:

“Some people are really rewarded by food, and some people just aren't that rewarded by food. Sometimes you see those people that just sort of forget to eat. And other people are like, how could you forget to eat? Some people just aren't wired to be as interested in food as other people. And it turns out that the next step is that some people when they eat are really highly rewarded by food. And some people aren't. The people that aren't very rewarded are like, "No, that was great. Thanks. Moving on. Not that exciting." And other people are like, "Oh, wow, that was fantastic!"

Yet the individual and diverse experiences of appetite are related to each other within the communities we participate in, the cultures we live within, and the social norms of hunger and eating that are enacted within these domains.

cold lunch

At a recent all-company virtual meeting in my 9 to 5 job, remote workers could order a lunch and expense it for attendance. I ordered a veggie burger and fries, which felt like the perfect hot meal for an iron-deficient pregnant gal during a dismal and cold March afternoon in Ontario. I plated it with the intention to eat camera off through the conversation. When the meeting started, we were asked to all keep our cameras on to participate. I watched the digital room with interest, noting not a single attendee was chewing on camera, despite the promised lunch. There was no outright verbal communication that we shouldn’t eat our lunches while on camera, but no one did.

I quietly messaged some coworkers to see if they were also trying to figure out how to subtly dig in to their food orders A few were, and we all had foods we didn’t feel comfortable scarfing back on camera: a gyro, a soup and grilled cheese sandwich, and a burrito. It struck me that these foods were all handhelds, implying messiness, gooyiness, melt in your mouth moments that require some level of intimacy or comfort when eating in public.

This was centralizing to my thoughts around lunch in Western contexts, why we’re so often pulled towards the cold foods that have been described by Chinese social media users as the “lunch of the suffering.” Harshly chopped salads, boiled eggs, raw vegetables, or cold sandwiches denote the lunches of the North American busy-folk. Lunches in corporate settings are a pinnacle of how Western society operates, calculated to be cold, quick, flavourless, and functional. I’ve written before around the particularly millennial urge to optimize life (for better or worse), and the corporate lunch maintains the speed and efficiency needed to perform optimally.

This experience made me laugh, mostly because I am too pregnant to really care if people see me chomping on a burger the size of my face in a formal, professional setting. Yet it also aligns with reports on how working professionals in America take their lunch: solo, and at their desk.

In a report for the New York Times in 2016, Maria Wollan highlighted that approximately 62 percent of working professionals ate their lunch at their desks, and nearly half of American adults ate their lunches alone. Millennials were flagged as a particular group of solo-lunchers due to their preference to multitask better. An anthropologist interviewed in the piece found through her ethnographic studies of white-collar eating habits, that “the way people eat at work is pretty sad.”

The pandemic influence on corporate office function has shifted so that remote and hybrid work styles are more accepted. With that, there’s a reduction in collaborative and social elements of dining. Everything is built to be optimized for work output and utilization. Even within my academic job, eating as a social practice was challenging throughout the day, barring a special occasion like a thesis defense or colloquium series. Outside of trades work and labour-driven jobs that require physical rest and hearty lunches to fuel work, there is just something so deeply entrenched in the North American lifestyle that necessitates single-serve food items, to-go coffees, breakfast bars, and plastic shaker salads for lunch.

I’m not trying to skirt around the idea of busyness as the sociocultural norm that strips our lunches of meanings in its relation to capitalism, but I also find the internet’s discussion of late-stage capitalism to be flat in their scope. It’s an easy given – of course we’re working this way, because late-stage capitalism. I agree, but I also think we’re stripping society down to one concept rather than looking at the intricacies within this system and how they all work in tandem to perpetuate isolation. What are the consequences of a capitalist workforce on how we understand meals, dining, and social gatherings? How does it impact workplace, and in turn, how does it shape individual relationships with lunch foods?

lunch of suffering

Last year, Chinese social media users took to a “white people food” trend, where they commented on American-style lunches after a video went viral commenting on low-effort and vegetable-heavy meals. White people food had three main components, according to some social media users:

First, it has no spices (“zero feeling to your food”) because it does not prioritise enjoyment. Second, it involves as little preparation as possible: “Eat it raw, eat it as a whole piece.” And third, it is eaten at work or school. “The idea is when you get off work, you go back to eat your normal food and you feel the life back.”

The jokes around the rabbit food grew increasingly more hilarious, with one Weibo user captioning their Lunchables experience pointing out how the unsatisfying experience reminds them of how alive they really are:

Yet the trend also challenged the more labour-intensive meals that Chinese young professionals would make at home, using many more ingredients and flavours. White people food became a “welcome change of pace” for some. On lifestyle sharing app Xiaohongshu, some captions suggested that the lack of carbs involved in these Western lunches helped with focus and reduced drowsiness.

There is a regularity to it, again an optimization to perform at a peak level for long periods of time without the ideas of warmth or more cultural nourishment informing what makes for a good lunch. Even still, discussions within the white people lunch trend eventually speak to what makes for a “healthy” lunch.

That the language of healthism sneaks into the idea of white people food, or Western lunches, or corporate lunches, feels like no mistake. At its core, the American, Canadian, and European standards of sandwiches, salads, and chunks of vegetables with dips speaks to how we value time, labour, community, and self. It prioritizes work, efficiency, and busyness over multiple cultural knowledges and narratives that are built into the foods we grow, produce, and consume.

Take the classic joke of white people making the same dinner during meal prep five days in a row: a cooked and unseasoned chicken breast, blanched vegetables (carrots, green beans, maybe broccoli), and some potato or rice starch. Add salt and pepper if it’s not too spicy. Quick meals to prep, removed from cultural and culinary histories, are devoid not only of physical flavours but the flavours of life itself.

They represent the notion of food serving only as fuel and speak to the bioessentialism that runs rampantly through the belief systems of white communities in the Western sphere: that behaviours, interests, or abilities are more biologically determinant than shaped by culture and society. When the world is taken at that face value, and food is removed from its sociopolitical context in lieu of bland white meat, it then opens the door to power dynamics that violate the humanity of people in the global majority, as well as sexual and gender-diverse communities.

That’s why I still think it’s more interesting to dig into the question of how when faced with the blanket response of late-stage capitalism. Yes, capitalism works to isolate and fracture the idea of communities to maintain power dynamics. But how this happens, and where it trickles into our daily lives, is the part that helps me unpack it more in practice.

As I finalize this essay, I’ve been eating a fruit salad that I made for my daughter and I as a late-morning snack. It’s Good Friday, so everything is closed, and we are leaning deeply into having a slow day. My husband has more energy than we do, and comes in just as I finish eating my snack bowl of chopped fruits and yogurt.

“What do you want for lunch?” he asks, smiling while knowing the inevitable.

Thank you for reading! You can find me on Instagram, Threads, and TikTok, or check out AnthroDish podcast on iTunes and Spotify.

This newsletter covers issues around food, health, identity, and environment, with recent topics like making sense of girl dinner, whether Athletic Greens is worth the hype, and how Mormon mommies have dominated the health space on Instagram. It is updated biweekly, and includes two additional posts for paid subscribers (usually a podcast sneak peak, a recommendation round-up, and transcripts from popular podcast episodes). If you enjoyed this and would like to support my work, please consider becoming a subscriber: