i still don't know how i feel about girl dinner

and i’m not sure what it says about gendered eating and domestic labour beyond the confines of white womanhood

I won’t lie. I started sketching out ideas for this essay as a way of critiquing the Girl Dinner as a frivolous concept meal that essentialized gender. But then I kept reading and watching more about it, and became newly fascinated by the layers of gender, femininity, and race that it really spoke to. And the more I dug into it, the less certain I was of a particular stance about the idea itself. Is Girl Dinner a lighthearted subverting of the expectations of traditional housewife-womanhood, or is it a white-wellness-lite rabbit hole into disordered eating?

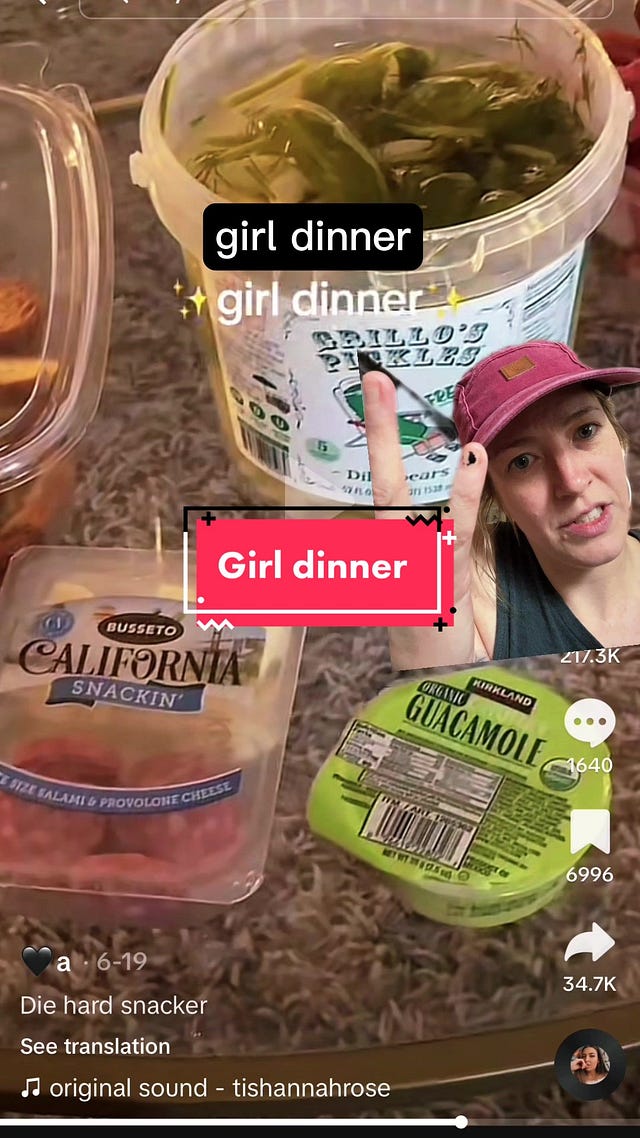

Girl Dinner, for the uninitiated, is a trend on TikTok where people that are too tired to cook a full meal-sized plate for themselves in the evening and end up throwing together scraps, snacks, and leftovers. It’s usually accompanied with an ear worm song about Girl Dinner itself, presenting a variety of thrown together no-cook or low prep foods, like frozen Yoplaits on a stick, noodles with salt and cheese, bagged popcorn, a slice of DQ ice cream cake, or a cheese string with boiled eggs and some strawberries.

As with any food trending on TikTok, there is a swath of articles chronicling its rise to popularity (Olivia Maher framing the medieval peasant dinner of bread and cheese as girl dinner), summarizing its many forms, and then explaining how to get the Girl Dinner filter on your TikTok.

The part of Girl Dinner that sits poorly with me is how unidimensional it is. Sure, it started as a bit of a joke, a push-back against the domestic expectations of young cis girls and women in American and Western society. But when you take a step back and look at the broader picture, it’s situated within the era of Hot Girl Walks, doing Girl Math, putting on Tomato or Strawberry Girl makeup, striving for Clean Girl aesthetics, and Barbie Girl feminism (is this a new wave of second-wave feminism? I’m not yet sure). We are saturated with Girl at a dizzying surface level in our current media cycles, but it is largely white, cis, and presumably straight young women (at least in terms of Girl Dinner in relation to boyfriend meals).

I was quick to initially dismiss the trend simply because I thought it was a little silly (the song doesn’t help). But then I remembered one of my biggest lessons from Dr. Emily Contois about pop culture and gender: that the very pieces of our pop culture that seem the most frivolous, goofy, and unimportant sometimes can speak more towards the deeper sentiments of our social and cultural structures than anything else.

So I got my Diet Coke and Ritz Cracker cheese “sandwiches” for Girl Dinner on a night where my daughter was away and my husband was at soccer, opened up my phone, and spent a few hours diving into the Girl Dinner videos to better understand what it all meant outside of the early peasant meal joke.

from punk-feminist to pickles and diet coke

Before TikTok, “Girl” steadily rose as a marketing construct from at least the late 1980s with Riot Grrls punk-feminist movements. While these are now looked at more as a trend itself in music, these political movements of teens and young women shaped a space in the music world where women could create their own rules, their own trajectories, and turn gigs and tours into safer spaces. As Kathleen Hanna’s Bikini Kill zines said, “We are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.”

Girl power was the natural extension of these punk-feminist spaces, soon becoming more mainstream with the Spice Girls and similar pop artists advocating for lipstick feminism. Yet the term itself, Girl, maintains the limitations that these early movements tried to fight back against. While Riot Grrls saw “girl” as a weapon to fight back against a society that drained women of their power, there were also men and older women using the term in more belittling ways.

Yet girls and girlies have steadily continued to serve a gendered narrative in storytelling and sociocultural experiences ever since. “Girl” is a powerful word for marketing stories, trends, brands, and all other sorts of capital. You see it across television shows in the aughts to now (Gilmore Girls, Gossip Girl, Girls, New Girl, 2 Broke Girls, Secret Diary of a Call Girl Good Girls, Paper Girls, Cable Girls, Derry Girls, and The Sex Lives of College Girls to name a few). I would also include Golden Girls, but they deserve their own sentence because of how their show predicated the rest in many ways.

Girl, in these examples, reclaims a particular space, time, and way of being that is otherwise nameless. Girl represents an experience that is still hyper-gendered, but a time in one’s life where the traps and pitfalls of womanhood aren’t quite as steady. In a 2016 essay, Robin Wasserman asks what it means when we call women girls, and highlights the more encoded messages within these girl narratives:

I think this is its key: the transition from girlhood to womanhood, from being someone to being someone’s wife, someone’s mother. Girl attunes us to what might be gained and lost in the transformation, and raises a possibility of reversion. To be called “just a girl” may be diminishment, but to call yourself “still a girl,” can be empowerment, laying claim to the unencumbered liberties of youth. As Gloria Steinem likes to remind us, women lose power as they age. The persistence of girlhood can be a battle cry.

If “girl” encodes transformative and liminal experiences, then Girl Dinner speaks to the more modern experiences of these liberties for young women across TikTok. One user (@shannonmarie) had an epiphany while talking to one of her girl friends about why the trend resonated so much with her:

The reason I have no thought in my brain as to what I want for dinner when my boyfriend asks… is… I don’t. I want to dilly dally in my pantry. I want crackers and cream cheese. I want Dotz Pretzels and a Coke Zero. Noodles and parmesan cheese at the most. I’ve been forcing myself to eat big meals because he wants dinner. I don’t want dinner! I want girl dinner.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Dilly dallying, exploring, and creating a space outside of one’s relationship to a man, partner, or child is a part of Girl Dinner that I find incredibly joyful and playful. It’s almost akin (in my mind) to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl us millennials had to combat in any romantic relationship during the 2010s, but with a more internal recognition rather than an external label-slapping by a No-Name version of Joseph Gordon Levitt.

Girl Dinner also runs in a blissful contrast to the momfluencer videos where moms bemoan the worst question you (or rather, their husbands) could possibly ask them every single day: “What’s for dinner?” I’ve written before about the relationship between wellness culture and Mormonism, and momfluencers fit squarely into this white hegemonic space where Christian Conservative values are being soft-launched online.

The ability to not cook, to not stuff oneself into the expectations of gendered labour that aligns with being someone’s wife or mother, is incredibly freeing. And for many reasons, the more traditional heteronormative expectations of earlier generations aren’t happening in younger generations: we’ve got moderately more accessible birth control (less kids, and having them at an older age), more secular society (less religious expectations about man and wife), more debt (less housing, more roommates), safer spaces for queer relationships and love (less strict gender binary experiences, fluid understandings of what makes a family), and you know, the ever-rising prices of food, gas, housing, and the marriage-industrial complex making for different paths and trajectories than our parents.

We’re not moving straight from being a young girl to someone’s 27-year-old child-bride (a la Broad City). There’s more ish in life, particularly in our twenties and honestly, even in our thirties onward (though as a 31-year-old, I say this tentatively).

essentializing the girlies

If you take the more recent trend of Girl Math, whereby TikTokers identify math that doesn’t literally add up but makes logical sense for “girls,” it’s perhaps easier to see the limits of ascribing gendered lenses to common experiences in TikTok. Say, for example, that you are returning an item of clothing at Zara for $50, but then spot an item while you’re in-store that has a ticket price of $100. You buy it, but really it only cost $50, because the remaining balance was already paid for by the return item. That is Girl Math. Or is it?

Feminist epistemologies tend to challenge more positivist philosophies, identifying women as knowledge holders in their own rights. Social positioning theories understand that experiences relating to one’s marginalization tend to create more knowledgeable understandings of particular phenomenon affecting them. For teen girls and young women, there are a host of social rituals and experiences that cause deeper reflection about their position in the world that shapes their knowledge experiences. But this experience isn’t something unique to those who identify as girls – nor unique to cis and hetero girls and women.

The transition from childhood to adolescence to adulthood is dripping in cultural understandings of what defines a child, the more novel concept of “teen” age in Western societies, and the rites of passage that lead individuals to adulthood. These experiences and rites of passage may vary by culture and community, but the understanding of liminal phases as individuals move from one social role to another with age is more global.

When girls and women in American and Canadian society are positioned as the sole community members that are capable of reflecting on their social conditions through these adolescent and early young adult life phases, it assumes that those existing outside these roles and age groups are not capable of reflecting on the world and their positions with the same ability or skill.

While these experiences of transitioning identities is important, limited English language maintains the fuzziness around the world girl. Anthropologist Dr. Susan Greenhalgh showcased English language limitations through the “girl/woman” terminology problem, in an interview with The Crimson (though please note that this interview was in 2013, and doesn’t address gender as a spectrum):

For college-aged 'males,' we have the helpful term 'guys,' which allows us to avoid both 'men' and 'boys.' For 'females,' there is no similar term (the comparable term, 'gals,' having gone out of fashion a long time ago), forcing us to choose between 'girls' and 'women.'

What does that mean for the experiences of non-binary and trans youth coming of age, without at-the-ready terminology? It certainly does not hold boys accountable to the same standard, despite having additional terms to use for these stages in masculine contexts. And at what point do you officially shift from girl to woman - if ever?

Without sounding like a Britney Spears song, this language problem only aids in maintaining the limbo of identity transitions that young people experience today. This might be felt even more for those growing up in families with very heteronormative and traditional/Conservative values. In these family roles, it can be much harder to stray from the prescribed values and domestic duties assigned by gender.

where girl dinner pushes back

The idea of marketing to “the girlies” has a foothold in mainstream media as well, with a noticeable preference for the girlies over the women performing particular gendered and/or “wifely” duties. As Rebecca Jennings writes for Vox,

Girls are not yet women and therefore less easy to despise. Girls are more available for consumption, and girls have more available to them.

Girls are more open to marketing, perhaps simply because they have more resources and finances available for disposable fast trends and marketing campaigns than a mum with a messy bun dragging her kids to swimming class after a full camp day. For the messy bun mum, trends may seem more like naming uninteresting habits for the sake of making it go viral, and feel less pressing. Or they could feel freeing, but less accessible given the clear parameters of youth and domestic labour roles (and fear of being called cheugy).

One TikTok user, Laura Danger, identifies how Girl Dinner contributes directly to conversations about the oppression of straight and married women in particular. She outlines how from very young ages, these women were taught to keep a pleasant space, and internalizing that standard in preparation for the social expectations of being someone’s wife.

Growing up, I was expected at our Sunday family dinners to perform simple pre-meal tasks, like setting the table, asking dinner guests what they’d like to drink, and then later serving dessert, all while my brother sat slumped in the couch watching sports highlights. As Danger says, despite it being broad strokes data trends, there is evidence that how children are raised by gender (and how girls and boys take responsibility for tasks) can "end up bleeding into adulthood.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Woman, then, feels like a much heavier term to use to define the self. It is particularly ladled with social value for generations that are coming into adulthood facing massive inflation costs for food and housing, and the haunting of a recession looming in the backdrop. Woman implies having one’s shit together, and having everyone else’s shit together, too.

unbearably white girl dinner

As with many parts of pop culture feminism this summer, Girl Dinner is also really, really white. Representatives for the various TikTok trend camps of Clean Girl (Hailey Beiber), Barbie Girl (Margot Robbie), and Tomato Girl (Italian girls) upload white standards of beauty, morality of the body, and power. Girl Dinner is really no different – albeit in snacking form rather than pure bodily focus. It also, in an interesting way, has the ability to situate white norms of the body into less charted territories of the girlies – the ones who are socially now allowed to be more of a mess, but that are unknowingly also upholding that they have to be cute in the process.

Amanda of Public Library on SubStack has dubbed 2023 White Girl Summer, and notices that the passage of time from COVID summers of three years ago to now has seen a tremendous reduction in white women’s active interest in centring Black voices:

Ultimately, history works in patterns and progress will always be met with (white) resistance. In the years since 2020, support for BLM has steadily declined...and so has the patience of white women hungry to return to their main character status.

Furthering whiteness within TikTok is the maintenance of body ideals through food trends. Even when started in jest, trends have the potential to be pushed to extreme depictions for the sake of a joke or due to the mindset of the person creating the video. For Girl Dinner, whiteness and thinness seem to go hand in hand. As the trend progresses, even other TikTok users are beginning to identify that Girl Dinner opens another door to diet culture for Gen Z.

Users adding the Girl Dinner audio more recently have been depicting “meals” that consist of ice cubes, or a single French fry. I even saw one video where the woman licked her salty tears as her “meal” to the audio overlay of the Girl Dinner song. Surprisingly (to me), no one has crossed meme-worlds and suggested the handful of 12 almonds their supposed-mums would suggest.

In the video from earlier about boyfriend meal dynamics, there are user comments beneath it about weight gain when eating what their partners eat, how they lost weight when they became single, and how Girl Dinner prevents their bodies from fluctuating away from thinness. The common thread is that the male gaze desires thinness, but living with the gazing male implies weight gain after sharing a meal at the end of the day (I wish I was exaggerating). Girl Dinner takes on a new meaning if it means maintaining a body that is not that of someone’s wife, girlfriend, or partner.

Now that Girl Dinner has been out a while, there are also users identifying that the presentation of snack meals as the usual reality for dinner can be damaging as well, particularly for those who are in eating disorder recovery. But to what extent this is heard by the louder crowd remains unknown.

the limitations of a snack for dinner

Ultimately, Girl Dinner is a snack for dinner. And snacks for dinner can be great, sometimes! When I was single parenting, I would often make my daughter something off her limited menu of “okay foods” and then grab some pickles, cheese, and bread and plop myself in front of my laptop to watch a dumb TV show after she went to bed. It was glorious – no rules.

I’m not saying that Girl Dinner is intentionally nefarious, evil, and twisted. I’m not saying I hate it, as there is good commentary and playful pushback about the social expectations awaiting young adults facing adulthood. But alongside that, it speaks to the white and Christian undertones shaping body and gender politics in 2023, which does not feel coincidental given the rise in anti-abortion laws, anti-trans laws, and pushes for more Conservative wifely behaviour for women. If you’re up for it, just search #TradWife and you’ll see what I mean – but you’ve been warned, it’s a lot.

The social undertones that shape Girl Dinner as a trend value whiteness, cisgendered, and heterosexual experiences of girls and girlies, and thus start to shape the ideals of coming of age in the 2020s, even when that process is less unilinear than in the past.

But also – it could also just be a good, fun, or joyful snack break amidst the performative social and gender roles of American culture instead of a specifically niche experience. I’m still not quite sure.

Other News: AnthroDish podcast will be back with a take 2 of Season 8 this September! As a way to celebrate, I will be publishing transcripts of listener-favourite episodes and sneak peaks of upcoming audio-interviews for paid subscribers each month.

Later this week I will be publishing the first transcript in the series, with food and culture writer Shailee Koranne (of Midnight Snack on Substack). Next month’s transcript will be for paid subscribers only due to the cost and time of transcribing. If you’d like a paid subscription but can’t afford it, please email me at any point (email below) and I will happily compensate.

If you listen to the podcast and have ideas about future guests or topics, I would also love to hear from you! Please email anthrodish@gmail.com with any suggestions.

Really loved this analysis!

Thanks for your work with this piece.