hacks, frauds, and ultra-processed people

or, food moralization, over and over again

“A hack is someone who does the same thing over and over.” So says Ava Daniels in the most recent season of Hacks. A hack job is also performed by someone who is not good at what they do: rough, irregular, short blows, with little precision or expertise.

Yet when hack is situated within nutrition (or at least the online discourse), it somehow mutates towards a desirable goal, linking body and technology through Internet language. Hacking the mainframe is sticking it to The Man, biohacking your body to align your physical experience with social ideals – despite being told they are impossible to reach. Or, as infectious disease expert Chris van Tulleken argues, foods can hack our minds — for the worse.

van Tulleken is the author of Ultra-Processed People: Why We Can’t Stop Eating Food That Isn’t Food, and at the (self-induced) centre of recent discussions around ultra-processed foods (UPFs) discussions. These UPFs are foods that are corporately engineered to include excess additives, emulsifiers, modified starches, and high levels of salts and sweets. The predominant tone is that people are getting addicted to heavily processed foods, which will hurt their long-term health. Absent from this are questions about how foods are coded as either trashy ultra-processed or elevated health food alternatives, depending on who is being considered.

ultra-processed chris

Since UPFs are pummelled with additives, the logic of vilifying them is that these additives can “hack” our brains to disrupt normal appetite regulation.

It’s an enticing sell, and a successful PR campaign: van Tulleken will sometimes use his body, and that of his twin brother Xand (also a doctor), to demonstrate how months of exclusively “bad” eating (only UPFs) takes a significant toll on the body. Chris compares his nutrition levels to that of Xand’s, and this single case-study is apparently enough to embolden the nutritional world to recommend avoiding these urgently bad foods – you know, the bagged breads, pastas, and crackers we’ve spent decades eating.

Questions about how much food processing is too much could be interesting, if handled respectfully. As a species, we use food processing to make sense of the food around us, enhance nutritional quality or safety (such as milk pasteurization), or to foster evolutionary growth (such as cooking foods that shaped early modern human brain size). It’s a part of how we shape our cultures, maintain our food inventories, and learn.

But as van Tulleken shapes it as an intimidating call towards food elitism. He has built a public image rooted in mythologies of self that make me pause, ones that have a direct through-line to moralizing body panic discourses. When asked to describe what started his interest in the matter, van Tulleken describes his experiences working with swaths of youth dying by infection in a vague Central Africa:

“And the reason they died,” he says, “was not because we lacked antibiotics. It was that they were being fed baby food made up with filthy water… milk formula was directly marketed to families as aspirational.” The more he witnessed of this tragedy, the more it became clear that “the solution should be to try to limit that corporate [marketing] power, rather than needing more antibiotics.”

The white saviourism is troubling on its own: the esteemed white doctor identifying appalling conditions in un-named African countries, homogenizing experiences of many diverse populations, and being horrified at the number of deaths and diseases.

An insidious problem here is infant formula deaths. The health issue it is not centering the dirty water, the colonialism, or the environmental racism. It is primarily because the formula itself is industrially processed!

Formula is a modern advent, and a lifesaving one in many situations. There are complexities to it, like Nestlé’s formula dependence-building, the aggressive marketing, and unethical targeting of mothers in lower income countries. But it’s striking that infant formula was what spurred van Tulleken’s lasting interest in UPFs. Environmental conditions persist that are unliveable, but a parent using infant formula to feed their newborn is the problem that needs to be tackled, apparently.

slippery definitions of ultra-process

Beyond its tenuous origin story, the UPF discussion is challenging in its very categorization of foods. What constitutes an ultra-processed food (compared to a processed food) is slippery in many ways.

The NOVA classification is used to determine ultra-processed foods from regular foods. In it, the focus is less on overall nutrient intake, but rather the extent of processed foods in an individual’s diet. The NOVA system is a recent public health strategy to assess dietary relationships with chronic disease. It argues that “what is done to foodstuffs and the nutrients originally contained in them, before they are purchased or consumed” is the most important factor shaping health now. Potential chronic health effects are connected to long-shelf lives, addictive ingredients, and heavy advertisements that surround these ultra-processed foods.

As I’ve written about before, food metrics are useful when you want to build comparative research, but they are bound by Western scientific understandings, and exist on a spectrum. Ultra-processed foods are emphasized to mean junk foods, indirectly. This challenges a lot of ultra-processed foods that are needed in certain conditions – such as food aid drops to Palestinians facing famine and genocide.

The term ultra-processed food emerged around 2011, through a long-term study of Brazilian households by Brazilian epidemiologists. They broke household foods into three general categories: unprocessed or minimally processed foods, processed culinary ingredients, and “ultra-processed ready-to-eat or ready-to-heat” food products. The study found that UPF consumption increased through time, including foods that had less fibre and more sugars, saturated fats, and sodium. The team identified the need for regulatory interventions around UPF abundance to “reverse the replacement of minimally processed foods and processed culinary ingredients by ultra-processed foods” in grocery stores.

The call to action is significant, though appears unheeded as awareness and urgency around UPFs grew. van Tulleken notes that the actual definition these Brazilian researchers put forward is “pages long because it needs to encompass so many different products. But if you’re trying to work out if something is a UPF, a good rule of thumb is that it’ll be wrapped in plastic and contain an ingredient you don’t find in a domestic kitchen.”

It's this pivot, simplifying and crisis-inducing, that frustrates me. Instead of putting pressure and responsibility on the industrial companies creating these foods, or the governmental bodies that can regulate costs and access (somewhat), NOVA advocates demand warning labels, and spew out op-eds that blame individual consumption choices for bad health. I’m not denying the science or the potential health issues around UPFs, but I find the emphasis on who’s to blame reminiscent of the 2000s “war on fat” campaigns.

NOVA policy is to avoid ultra-processed foods altogether for good health, and to reject reformulating UPFs to enhance nutritional quality. Michael Gibney illuminates this rigid strategy limitation through infant formula: NOVA expects the promotion of exclusively breastfeeding an infant for the first six months, and then requires “carers to be responsible for the direct preparation of such foods from unprocessed foods” during transitions to solid foods.

It’s an all-or-nothing approach that contrasts with reality, which is that at least half of daily energy intake for Western populations is made up of UPFs. If the Reagan “don’t do drugs” campaign demonstrated anything, it’s that abstinence doesn’t work. It maintains stigma and shame around food, drugs, alcohol, and sex that permeate into everyday lives.

The trouble with slippery definitions and rigid policy directives for food is that they can be warped for the definer’s agenda. Some ultra-processed foods are coded as white and safe, and some can be coded to be negative, because they are associated with Black and other POC communities, or poverty, or both. If you can tweak a definition to suit your needs, you can keep changing the baseline to stay unattainable.

moralization & shame

When experts lambast particular foods as inherently bad, a logic develops around those who eat it, where they end up stigmatized and made to feel ashamed of their circumstances. Western healthism has dominated our understanding of foods and the body for the 21st century, where values of food are assigned socially, but felt personally.

Dietician Jessica Wilson has been vocally challenging UPF discourses, particularly the idea that you could “take back your health” if you avoid them. The idea that health is something to take back assumes privileges of health, finance, and food, ignorant of racialized and class-based barriers. Wilson looks at the examples of UPF foods given in these discussions, which implicitly tell who is and isn’t allowed to eat ultra-processed foods. Examples skew toward the poor: Oreos, Domino’s deep-dish pizza, and Wonder bread are identified as foods that cause damage to our physical and mental health.

But what of the ultra-processed foods you can find in high-end grocery stores? Smart Sweets, Poppi colas, and Nut Thin crackers all have health-washed labels that tend to slip away from UPF critique. Wilson posits that these are coded languages, with the goal to make people scared and maintain power through racial and class-based food categorization.

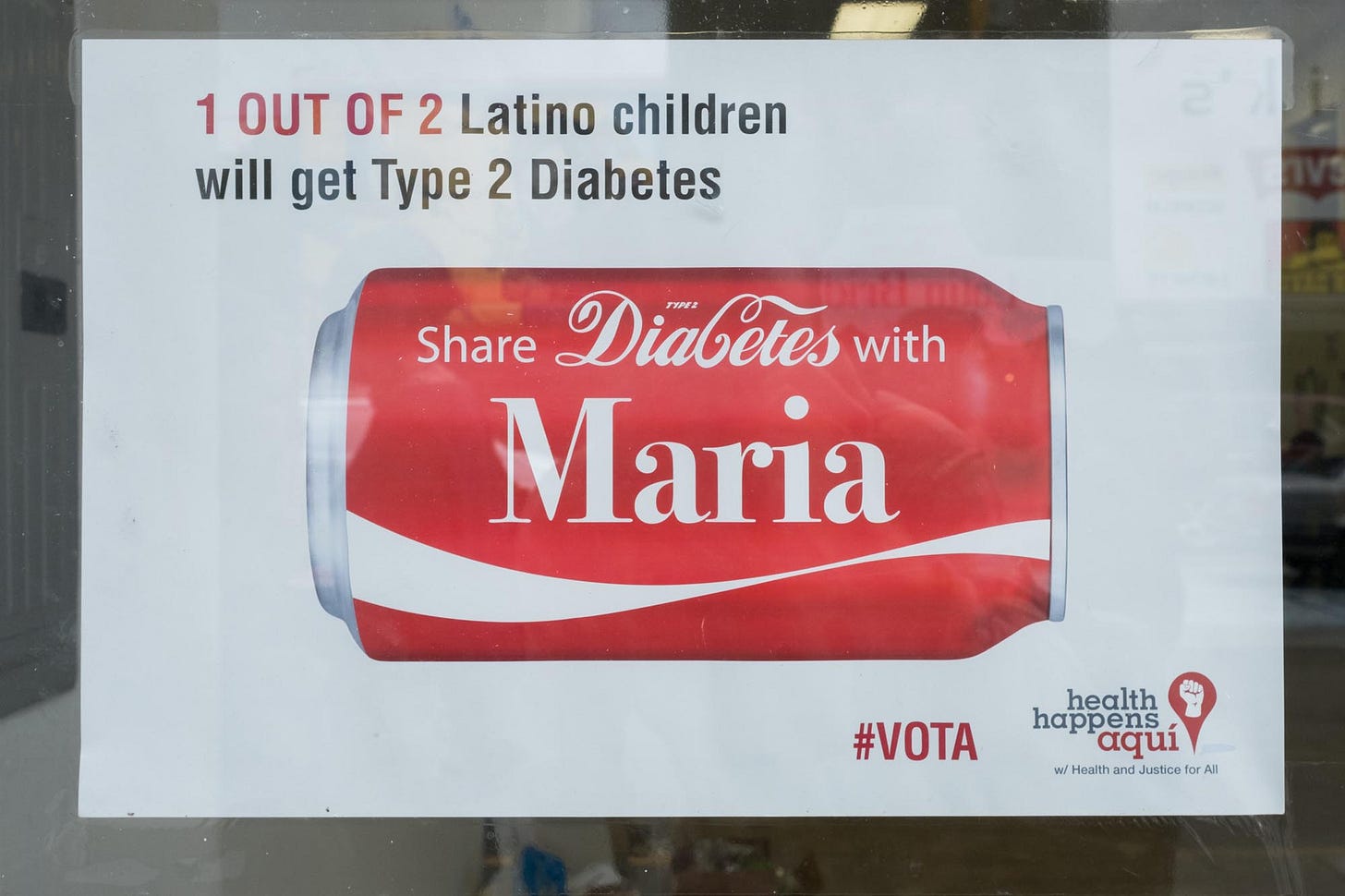

Wilson maintains that race cannot be separated from nutrition policies: she provides the example about how white-coded foods and beverages, like the fibre soda Ollipop, are encouraged as healthy alternatives to alcoholic beverages. They aren’t threatening foods, because they won’t “give Kevin and Carly diabetes.” But as Wilson says, when non-alcoholic beverages “come from a corner store, and are associated with Black and brown children? That’s a problem.” Health campaigns explicitly target through racially profiling: “Share diabetes with Maria. 1 out of 2 Latino children will get type 2 diabetes.”

This is particularly felt through the anti-fatness language in these campaigns. Much like wellness culture being a glossy update to 1990s diet culture, ultra-processed foods allow for health experts to maintain their own fatphobia. By presenting certain processed foods as bad, you put forward associations of body size, race, and class, all without having to directly address these. Yet studies in France and the UK have so far not identified correlations between ultra-processed foods and BMI. This is food moralization, not an advent of health.

cost of living crisis, not food crisis

The reality for many people is that we are struggling to afford groceries. As Tressie Mcmillan Cottom identifies, while economic lives tend to be painted by unemployment rates and low wages, the reality is that there isn’t enough housing. We are struggling to afford life! What better time than now to swoop in with a sensational argument about foods we must eat, and make us fear our own lack of control?

Two elements are important here: people are struggling and need affordable foods, and the evolution of processed foods is not an inevitability. Many food categories in the grocery store are monopolized, prices are fixed in schemes between grocery retailers and distributors, and slotting fees and advertising budgets claim prime retail spaces to dominate consumer attention. I don’t situate my writing as a place where we must accept low-quality ingredients in our food as inescapable, but I do think focus needs to sharply pivot away from people-as-consumers and towards monopolies, multinational companies, and policy regulations that provide feasible transitions to affordable and adequate foods for cultural and physical health.

Ava’s description of a hack is suspiciously close to Einstein’s definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different outcomes. In some ways, the writers, scientists, dieticians, and healthcare providers fighting for some nuance about food are the ones pursuing insanity. Particularly in a culture that is hell-bent on demonizing some foods and proselytizing others. As many have pointed out before me, which foods are framed as UPFs are tailored to fear-monger and sensationalize the limited food options made available to vulnerable populations – those living in states of food apartheid (or real apartheid), those experiencing famine, Black and Brown communities, and poor families. Annie’s Mac and Cheese is no better than Kraft Dinner, but it’s got bunnies and organic logos slapped across the front, and costs more. If one thing is true amidst all of this, it’s that we’re all tentatively culpable of buying our way into food morality.

Or maybe – the hacks are the ones trying to sell snake oil again and again and expecting different outcomes. Maybe they wait until a new generation, using a new medium, can have purchasing power, only to scare them into making purchases that simultaneously up their credit card bills (“de-bloating” tummy pills are Gen Z’s detox teas). Doing so manufactures a crisis, circumventing those responsible for the abundance of high processed food: multi-national corporations, industrial manufacturers, and grocery CEOs and retailers.

Thank you for reading! You can find me on Instagram, Threads, and TikTok, or check out AnthroDish podcast on iTunes and Spotify.

This newsletter covers issues around food, health, identity, and environment, with topics like making sense of girl dinner, whether Athletic Greens is worth the hype, and how Mormon mommies have dominated the health space on Instagram. It is updated biweekly, and includes two additional posts for paid subscribers (a monthly interview transcript from popular podcast episodes, and a recommendation round-up of shows, books, and podcasts).

If you enjoyed this and would like to support my work, please consider becoming a subscriber:

AnthroDish Podcast News:

I’m slowly starting to dust off the microphone from summer break, and have put out a call for booking interviews for the ninth (!!!) season of the show, scheduled to start airing in late September. If you have any ideas for guests that want to chat about their research, writing, and experiences around food and culture, feel free to send me a message!

Paid Subscriber News:

August’s paid subscriber interview will be out on August 18th. It will be a transcript of a conversation with LA food stylist Alyssa Noui, where she explores how to translate flavours and textures through visuals, and how she navigates the risks of food waste while filming cooking scenes for film and television.

Loved this article! Now that groceries are considered a luxury, it widens the gap between people who have access to healthy food and those who can't afford healthier options.

Thank you for this punchy, going to the heart of the matter article. This is an issue some of my colleagues have written about too as part of a Food and Health related project in NZ. Do take a look when you get a chance: https://ourlandandwater.nz/project/aotearoa-food-cultures/