That my kitchen is ugly should not matter, yet it’s ugly enough that I’ve given it considerate thought.

My kitchen is illustrious in how it came to be so dull, one whose hands have changed over several years (if not decades) through student rentals, until it fell into my husband’s. It is a product of its time: the landlord specials of the early 2000s rather than the millennial greige of the last few years. Deep brown cupboards, no doubt painted this way assuming they could effectively hide cooking stains (it doesn’t). Silver almond-shaped knobs adorned with mysterious splotches of sauce, and dents and scratches from the many who briefly encountered meals in this home.

Six pot lights stretch in two rows across the white ceilings, failing and sputtering out every few months, this makes it impossible to take food photos without creeping shadows. (This seems superficial, but it makes posting anything related to the podcast or PR challenging). In between these lights, there is a white ceiling fan collecting dust, its knobs rusting from lack of use (our lack of care),. Were it ever turned on, it would harshly slice the rays of light coming from the ceiling. We can’t turn them on, as my husband points out: it would risk a strobing effect for someone like myself, a former epileptic. Perhaps that is why I hate the lights so much—misplacing frustrations about the limitations of my body, the limitations of a space.

When I saw the Pantone 2025 colour of the year, I was shocked: mocha mousse is the very colour that cloaks our ugly kitchen. Pantone describes it as “a warming, brown hue imbued with richness” that “nurtures us with its suggestion of the delectable qualities of chocolate and coffee, answering our desire for comfort.”

I look at these aging rental walls in the kitchen and laugh hysterically.

writes of the hidden soft power behind these delectable takes on mocha mousse:also spoke to what mocha mousse exemplifies in our cultural values, noting that while it looks like a shit whipped into a frothy dessert, it also exposes forms of quiet luxury:“The Pantone colour of the year … is the indulgently named ‘mocha mousse’, but it really isn’t what it seems. It never is… The word choices are careful and considered, there is the comparison to chocolate and coffee, to the moralities of consumption around comfort, but also to an expression of ethical consumption which is often the case when talking about chocolate and coffee en masse to subvert the limits of solidarity, labour, and justice.

To call the language surrounding quiet luxury “class-coded” would be redundant; class signaling is the entire point. Acolytes will also describe the opposite of quiet luxury as “tacky.” Big and/or ostentatious logos are gauche, very “new money.” You want to avoid clothes that are “too” tight or baggy, bright colours, and animal print. (All the things I live in, essentially.) That’s the “aspirational and luxe” that Pantone is talking about.

Our desires for comfort, our aspiration for enough wealth to one day own a home of our own, all of these are pieces of anxiety we greet each day in our rented kitchen. Teniade argues that “cloaking your home and body in beige and mocha mousse won’t make the wealthy accept you into their ranks.” But as both authors point to, these are soft and quiet forms of power, like a brown noise machine playing out across housing spaces. What happens when it’s the landlords that have bathed your home in aspirational mocha for you?

***

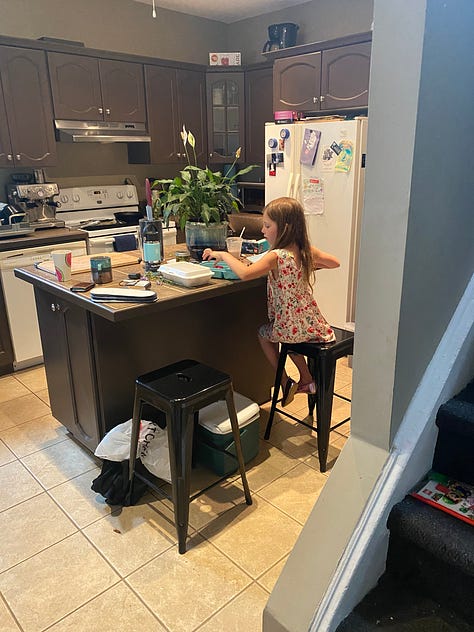

In truth, our whole home was painted this brown before we moved in, but it feels especially muddy in the kitchen. While it has a wide kitchen island, it is challenging to move around in—particularly if the home is designed to fit at least three, sometimes five, renters at a time. How we ended up here as a family is a testament to my husband’s long-game patience, which is why I love this home as much as I do.

In the early days of dating, I would visit him here on weekends. I’d sit nervously on a tall chair at the kitchen island, hands tracing the (surprise, brown) floor tile used as countertop, mapping the divots and cracks and patterns, avoiding eye contact. I was broke and anxious and tired as a single parent, unsure but hopeful of what this relationship might be. He would dice carrots, mushrooms, zucchini, onions, play D’Angelo on the speakers, and pour a glass of wine for me. He was quiet but sure, somehow leading me outside of myself.

The kitchen was our meeting space, and there was comfort in the familiar tasks and smells, of cooking oil and coffee and toasting bagels when I still didn’t have the language for a blended family. It was the space he knew I could open up in. His roommates at the time would dabble, then quickly retreat to their corners of the home. The kitchen survived their coconut-oil baked eggs (a smell I wouldn’t wish on anyone), their empties and cigarette butts, or their musky, herby concoctions left to boil suspiciously in summer months—though these certainly left their lasting marks on its character. Adrian played chess while they played poker, secretly counting on their departures as a window of opportunity for my daughter and me to move in one day.

That the kitchen is ugly does not mean it isn’t useful—a lesson I learned the hard way. When COVID hit, I moved my daughter and I back to my hometown of Peterborough, in a two-bedroom apartment contained within the type of century home that Gen X landlords love to make into their entire identity. It had a backyard, a novelty after years in Toronto. That it sat on one of the busiest and most thieved streets I’d tuck away out of necessity. The Peterborough apartment had won me over for its kitchen, deep greys and blues, a two-basin sink with a rotating nozzle to clean big cookware with, sparkling black granite countertops, cupboards and a full pantry, quiet self-closing drawers, and a stainless-steel fridge! It was breathtaking, and it would be ours to cook ourselves anew in.

But aesthetics does not always translate to productivity. The kitchen proved to be a façade for a useless cooking space. No actual counter space to speak of for dicing vegetables or drying cleaned dishes, no place for my daughter to sprawl out over homework while I chopped up dinner. It felt beautiful to be in, but it did not make for effective use of time as a single mum. The whole apartment was cohabited by squirrels, clawing and chewing through the pantry walls, trying to sneak into our food sources. Beyond that, a crumbling balcony with six locks, an attic with live insulation, rusty nails, and gaping holes—I hammered a giant canvas print against that door, hoping that would scare off my daughter. The kitchen’s beauty had bewitched me, and I was a dumb Disney prince caught by its enchantment.

Moving from Squirrel House was a relief for many reasons.

***

I will never quite understand the transformation of kitchen from stranger to friend for me, as it was an unfamiliar place in my youth. It was reserved for sneaking chocolate chips or unravelling Pilsbury cookie dough on January afternoons for my brother and I. More than anything, it was a place where squeaks and guzzles and the breaking down of food in mouth drove my misophonia above ground and raging.

Somewhere between my childhood kitchen and now, I began to dream of it as a place to cook and bake potential with my hands. A place to ruminate on loftier dreams with my daughter, let them simmer alongside the pots or gooey double-chocolate cookies. A space to pause and transition away from the logged hours in my little home office (my own form of Severance).

With all those lessons, I still dream of a beautiful kitchen one day. I watch real estate shows to remember what could be possible. In Selling the City, neutral and pastel-clad real estate agents remark over a luxury kitchen with a pasta pot faucet. One agent doesn’t know its name, for which I am grateful—I’ve never seen such a faucet in my life! In response, the rest of the women glare, with one saying, “If you’re gonna sell luxury real estate, you gotta know what a pot filler is.”

Almost on cue, the listing agent intervenes about the pot filler, noting that convenience is a luxury. It is particularly true of the more aspirational kitchen conveniences—pot fillers, hidden fridges, under-mount sinks, statement range hoods, deep storage drawers, stone-top functional islands—which amount to an ease of navigating cooking and cleaning, though for who is a different conversation.

I watch home cooking shows and sit in awe at how pristine and peaceful they are, knowing these are either test kitchens or studio rentals, places that are immaculately kept with dozens of staff. There’s a façade to cooking in them, a performance for cameras and viewers.

An ugly kitchen is inherently not for a camera, but for the landlord’s pocket. Still, it has felt transformative for me despite its lacking aesthetics. I may get frustrated trying to take a before photo of the cute solid food spread I’ve prepared for my goblin baby, but that doesn’t take the life out of it. It just means that using the kitchen as a supplementary source of income becomes tenuous.

Yet this kitchen’s value lies in its ability to hold a space for all four of us. Not for the camera, but for making a packet of hot chocolate after a bad school day, for slicing apples and oranges to give a teething baby, for meal planning on post-its and slapping grocery hauls on worn countertops. For spilling formula, breaking water glasses, dropping an entire tub of blueberries, knocking over a bag of flour. For growing my many pothos plants, for displaying clay dragons on a windowsill, for piling cookbook mail on the industrial shelf we added.

It is a space for deep cleaning and acknowledging it will never be pristine, but it will be good enough (and a place to read The Good Enough Weekly, for

’s evergreen reminders). For a moment of pause with my husband while the world spins on too quickly for us—a place to find a sweet treat, a place to heat up leftovers, a place to microwave milk for an espresso shot. For cooking a Christmas meal for our entire family, baking cookies and giggling with kids on playdates, melting our days away with garlic, onion, and oil. For wanting and dreaming of more for ourselves and our children.Our ugly kitchen is ours: stained, storied, and at very least, sustaining.

AnthroDish Essays come out biweekly on Sunday mornings. If you’d like to support my work, paid subscriptions are $30 USD per year (or $5 USD monthly). Paid subscribers receive two additional Sunday newsletters per month: an AnthroDish interview transcript and a round-up of recipes, books, and shows of the month. There also are some additional fun perks coming later this year!

You can find me on Instagram, Threads, and TikTok, but I can’t promise it’s anything except random thoughts on any of those platforms.

AnthroDish Podcast News:

New episodes for the second half of season 9 are out now! Be sure to check them out on iTunes, Spotify, and YouTube. Latest episodes are full of great food ideas from some wonderful people I’ve connected with through Substack:

Food systems scholar and co-founder of

Isabela Bonnevera on the invisibility of immigrants in food systemsSommelier and

writer Sarah May Grunwald on the rich history of Georgian wines- ’s Shreema Mehta on under-utilized and climate friendly crops that support more biodiversity in the kitchen

Paid Subscriber News:

February’s paid subscriber interview was with anthropology PhD student Danielle Gendron on the gassier side of our food and digestion experience—and how she integrated that into her research on Indigenous food systems. (Also, the most challenging interview because Danielle is a friend, and this is inherently a very funny topic, but she brings some apt points into it).

I will be launching some additional paid subscriber perks as part of a working group with other Substackers—this information to be shared shortly!

When we bought our house there was no kitchen. So we bought an Ikea kitchen which fell apart in two years. Like it is peeling, has black mold in spots, rust everywhere. It's disgusting and I saved and saved and saved and after 12 gross years I am finally redoing my kitchen with a proper Italian brand. It wasn't just ugly, it was a health hazard.

Also, small round under cabinet lights are inexpensive though they do permanently take up a plug.