where do we go next for affordable and accessible food in Canada?

a rage dump of food in canadian news and politics this fall

When I last wrote about the soaring costs of food in Canada, the federal government was scrambling to tackle grocery store CEOs and their runaway profits. Since then, there have been loose loose political commitments to lowering food prices and reign in profits. There has also been a steady state of social surveillance while grocery shopping, and food prices hovering around much the same prices as March 2023. Well – they are higher, but what’s ten cent hikes at this point amidst the global chaos of genocide and climate change?

I wasn’t much wanting to dig into this topic again, out of exhaustion. Around a month ago, I started to notice even more grocery surveillance in addition to the placements of gates and security measures. Now, there are signs posted at the entry gates informing shoppers to expect receipt checks upon exit, as if everywhere is now an elite and bumping Costco Club. This was enough to make me scoff and not write more about it, but then I had an encounter with a woman outside of a grocery store that set my wheels spinning again in a stubborn and rekindled disdain for how much the Canadian government is failing its people right now.

The woman I bumped into had asked me to help her purchase some food. I could tell she was hungry and nervous to ask, there were many rushed Torontonians pushing past her already. She had mentioned the grocery store would likely pass a lot of judgement on us, so I nodded and asked if she wanted to come shopping with me. I’ve been flat broke in precarious points of my life – when my daughter was still on formula, I was not making enough to keep up with her dietary needs and was forced to get very scrappy. It was terrifying, and I made a promise to myself to help anyone in a similar predicament when I was in a better financial place down the road. Today, I thankfully am.

True to expectations, we were immediately hounded by the store manager and security. They warned me about the woman having done this before, the store manager eventually yelling at me about how the woman always gets “outrageously expensive food.” I stopped her right there: “And who’s fault is that, that 6 ounces of raspberries are $10? Hers or your CEOs?” The store manager scoffed and sent her security goonies to follow us the next ten minutes, despite us paying in full for everything.

I don’t tell this story out of pride – everything about this moment was awful, uncomfortable, and heartbreaking. I tell it because this is the scenario we are living in now, where hungry people are being villainized over their lack of access to safe and affordable food. Our food prices are skyrocketing, our food bank usage as a nation is at an all time high, and the Canadian government has yet to develop any direct, tangible path forward to reduce food inflation. We’re allegedly a progressive and good country to live in: we pride ourselves on our universal health care and kindly Canuck personas. But these personas feel increasingly further from the truth, particularly when it comes to food.

high food bank use, low food bank donations

When you think about what a food bank does, stripped of any romanticized notions, it is a non-for-profit organization that provides temporary relief through non-perishable food items. I’ve written before about the limitations of the concept of food security, and food banks directly relate to this for me. It is easier to talk about food insecurity than it is to admit that there are people living in poverty. And, it is easier to talk about food (it’s polite) than it is to talk about how much someone pays for rent when provincial governments have created rent-control loopholes, or what happens when someone isn’t able to pay their monthly bills. No one likes talking about money, but everyone loves the idea that food will “always” bring us together.

I vehemently disagree: food is a tool, it has and continues to be used as a weapon to control and violate ethnic populations. Look no further than the forced assimilation of Indigenous Peoples to Canadian food through the five “white gifts,” or the ongoing weaponization of food in Palestine.

In the realm of Canadian food security, food is one of the first parts of the budget to be skimped when financial pressures squeeze a family or household. Neil Hetherington, CEO of Toronto’s Daily Bread aptly described it:

"You've got food prices, you've got a precarious work environment, and most of all lack of decent, affordable housing," he said. “And you put all of those things together and suddenly you can understand why people are turning to food banks."

In the Food Banks Canada HungerCount 2023 report, they noted a 32% increase in food bank visits across Canada in March 2023 (compared to March 2022), and a 78.5% increase when comparing to March 2019 visits. This is the highest reported increase in usage ever in Canada. And while 28.8% of Canadian food bank users this year were receiving some form of provincial social assistance, roughly 16.6% of users were currently employed, and only 1 in 10 reported users received pension income.

Second Harvest (a national service that redistributes food waste for those in need) recently forecasted that 60% more Canadians per month are expected to be served by a food bank each month in 2023 than last year. They also indicated a 124% increase in over non-profit food bank use. Their reports summarize responses from 1300 non-profit food organizations across the country.

The message behind all these startlingly high statistics, is the reminder that food banks are not prepared for the surge in need and demand. It is dependent on volunteering time and food donations, the charity of some who can for some who cannot. Yet donations have decreased while families grapple with tighter budgets and the rising bank rates the last couple of years.

While the Bank of Canada has been pulling a British “Keep Calm and Carry On” mentality, insisting that the economy is cooling, the Bank still cites concerns that policy rates could increase, since inflationary risks have increased. (I will admit, I’m not an economist, all of that is bungle for me to wade through. Please weigh in here if this is your jam, I’d love to hear more about it!).

food inflation remains despite “cooling” economy

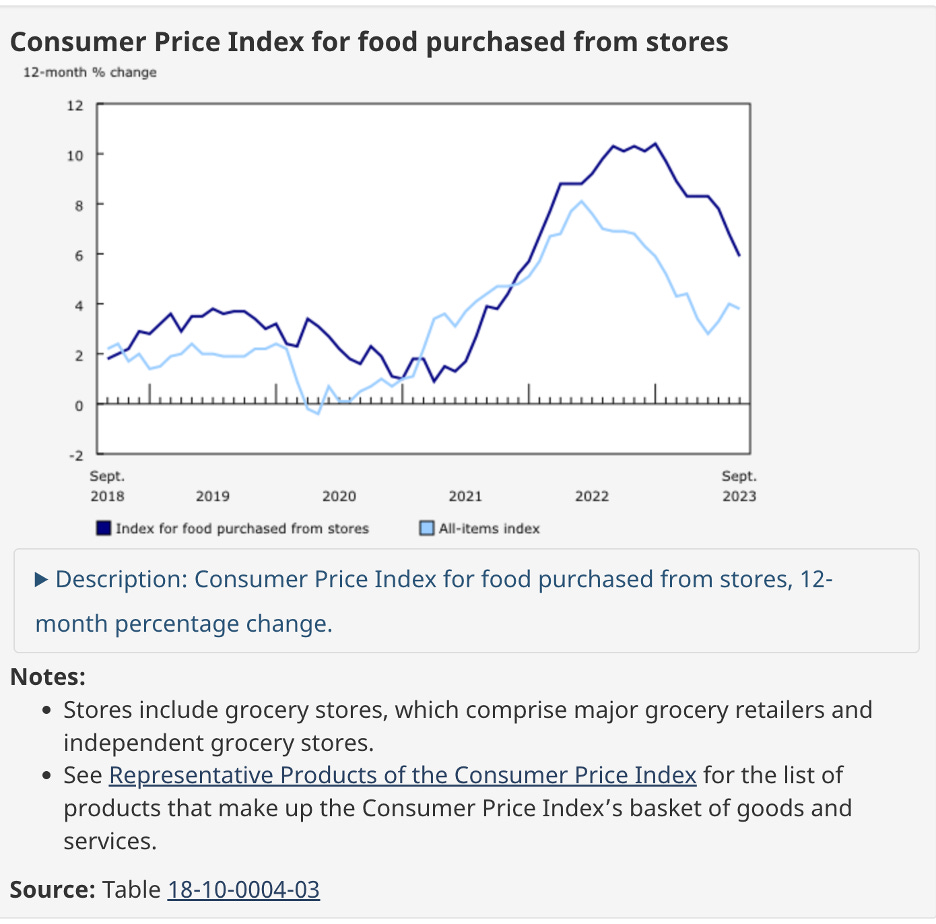

While the Bank of Canada maintains that inflation is cooling, grocery prices are continuing to outpace inflation predictions this fall. A new collaboration between Statistics Canada, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, and Industry, Science, and Economic Development Canada has launched a data hub to watch and compare food prices.

The goal of the Food Price Data Hub is to help us as consumers make “informed decisions about food purchases.” In reviewing it though, I would argue it is more helpful to us as humans for not feeling entirely gaslit when we see the price of Presidents Choice frozen pizzas jump from 2 for $6.50 to 2 for $9.00 in the span of a month.It takes the Consumer Price Index, or CPI (which is the main way to measure Canadian inflation right now) to look at food prices for items purchased at stores, including major and independent grocery retailers.

It’s not perfect, as prices vary from store to store, but it is a neat way to track changes to common food items:

It can also be used to assess the change prices through the food supply chain, such as looking at costs for producing livestock or maintaining farm machinery fuel, for processing and packing (I do find it odd to see plastic bags on the list when they’ve been banned in Canada), and for tracking the decreasing costs of truck transportations in comparison to the grocery store markup (that is an important one to clock in the figure below).

It doesn’t solve the problem, but it is a handy tool to monitor the data that paints itself into our daily lives or weekly grocery store trips. It is assuaging to me, but I know I am a data nerd. I already knew my weekly food bills escalated, but seeing the CPI graphs helps situate it in the bigger picture for me. Yet – it is only a start.

the food web with no net

For me, it is clear to see the connection between grocery stores inflating the cost of food products and Canadian households struggling to keep up. It is reasonable in the landscape of impossible food prices that those who were already living pay to pay are turning to food banks that we are told are there to help in times of need. Taken a step further, however, is unpacking why the Canadian government is also banking on food banks to provide for Canadians right now.

Canada is the only G7 country that does not maintain a national school food program, or any sort of national food program standards. After WWII, most of these G7 countries established school programs for children, to ensure some standardized nutrition at school. While it’s debatable how effective some of these programs are, there is food available.

Canada has always lacked in food policy (until 2019), and the food guide has been influenced by lobbyists over nutritional science. The post-war Canadian government, however, reasoned that families could rely on the family allowance program. This program ended in the 1990s and has been replaced by the Child Tax Benefit. Having been a recipient of that benefit, I would say it is certainly useful, but I usually used it on seasonal clothes, school supplies, or swimming lessons for my daughter over food. When you don’t build a specific food safety net into communities, it is up to the recipients to shape how it is used.

So school programs fall on schools to uplift, and many foreseeably cannot keep up with the need. Rod Allen of Nourish Cowichan depicts the reality that many face now:

"A lot of effort goes into finding volunteers, training them and so on. So if there was a little bit more dependable financial support, it might be possible to provide stronger infrastructure… The story we like to tell is that we're a middle-class nation with great social networks and a social net," said Allen. "I think that has been true, but … that story has allowed us to ignore so many parts of where that net has been failing over time."

Across the board, there is a clear need to address the affordability issues rearing their brute heads in Canada. The launch of the Food Price Data Hub should be the opening to a brighter future food food policy, but I’m not wholly convinced it will happen.

all talk, little action

Industry Minister Francois-Phillipe Champagne noted in recent and ongoing talks with gerocery CEOs, the major grocery retailers (Walmart, Costco, Loblwas, Sobeys, and Metro) had submitted their plans on how to stabilize prices amidst high inflation. Yet a few weeks later, the Minister then turned and declared he wanted to see more details from major groceries about what they will do before they do it.

The Canadian Competition Bureau investigated the high food prices this past March and identified that major grocery retailers are indeed excessively benefitting from food inflation, and that the grocery sector is largely controlled by Loblaw, Metro, and Sobeys.

Champagne maintains that “inaction is not an option.” Yet in his ongoing talks with grocery leaders as well as food manufacturers, there isn’t much action really happening yet. There have been five commitments announced and secured through the talks:

Grocers to provide “aggressive discounts across a basket of key food products, price freezes, and price matching campaigns.” (As an aside - all I’ve noticed are baskets of Lucky Charms, No Name Noodles, and Goldfish crackers, such as the main photo for this essay, sooo…)

The implementation of a Grocery Task Force (like the Avengers of food?) to tackle shrink-flation and other practices that hurt consumers in the food industry.

The establishment of a Grocery Code of Conduct

Improving the accessibility of data on food prices

Modernize the legislative framework of the Competition Act, which essentially would target the five major retailers firm grip on the market and open it up to more and smaller retailers.

I’d like to think this is a good start, but thinking back to the increased pressures on non-profits and charitable organizations, I’m still at a bit of a loss. I really see our social net fraying in Canada with affordability issues. I then also see its relationship to the increased homelessness, lack of mental health care and support, lack of harm reduction services, and increasing public approval for medical assistance in dying (MAiD) for those living with mental health challenges.

I think back to the woman I met, who shared her story (and with whom I shared my own, more deeply than I have here), and I wonder how and where community lies in all of this. Amidst the glossy visits by CEOs and politicians and all the others who are here to simply tell us the one story of food being the problem, they are missing just how fractured life in the COVID-era has become. They continue to miss the relationship between food access and money, poverty, and isolation.

I think, if I think anything at all of this whole mess, we need to seriously reconsider what the roles of our government are — how can we use our votes to shape a future where non-profits are supported and stabilized by consistent federal funding to the human right for accessible and affordable food? How can we push to have governments remain accountable to link food costs with affordability of living in Canada? I hate ending on a question, but it seems that is all I have these days.

What are your thoughts? Are you more optimistic than me? Leave a comment and let me know what you’ve been thinking about all of this.

Thanks for all of this - sharing your story, sharing your time and showing care for a stranger, sharing these links and stats (Neil is a friend from years ago doing important work!) - I am optimistic because of pieces like this and people like you both.